Can low tunnels extend your garden season into winter?

- Nov 30, 2023

- 10 min read

Updated: Apr 24, 2024

When people find out that we use tunnels to extend our growing season, it doesn't take long before they ask about growing vegetables in the winter. "Whoa whoa whoa...these aren't magic tunnels!" I say. Tunnels certainly make a difference, but they can't turn -30ºC into +20ºC. So no, we don't grow vegetables throughout our entire winter. In our neck of the woods, it's not realistic to keep our gardens growing all year round without an incredible amount of supplemental heat and light. That said, we still see the value of high and low tunnels, and to help you get a better idea of their realistic potential, we're going to look at some tunnel temperature data and track the progress of some cold hardy greens as they carry on under a tunnel long after our first frost.

In the past, I have used to use a few mechanical min/max thermometers to keep an eye on the high and low temperatures around my gardens, but the new kids on the block this season are some wireless digital thermometers. (see below) I've bought digital thermometers before that died all too soon and were irreparable so I was nervous about repeating this mistake. However, the set of Govee temperature sensors I acquired has not disappointed, and their fantastic temperature logging ability has been so valuable that I almost wouldn't care if they only lasted a couple of years. Hopefully, I haven't spoiled my luck by saying that.

What's so great about these temperature sensors? Well, they just do everything you would want a temperature sensor to do. They measure the temperature (and humidity), they record their own data continuously so you don't have to, and they can even alert me when temperatures fall outside of the custom limits that I set. I can check the current temperature readings of my sensors on my phone anywhere I have internet access, and even pull up graphs of the temperatures logged in the past day, week, month, or any other time period.

Armed with 6 of these temperature sensors, I set out this fall to explore the limits of our high and low tunnels. At first, I placed one sensor in each location (high tunnel, low tunnel, and open air) but would later add a second sensor in each location to help verify the accuracy of the data. The data collection kicked off on September 20th when I set up one of our low tunnels to extend the season over a couple of beds of spinach and kale. The video below shows our low tunnel setup.

That's enough of an introduction. I'll organize the rest of this post around a few guiding questions.

What are typical fall temperatures in Saskatoon, SK?

How well does a low tunnel protect our crops during a hard frost?

Can a low tunnel turn average November days into suitable growing days?

Once we have these answers, we'll be able to tackle the big question of whether or not a low tunnel can keep our garden growing through freezing

What are typical fall temperatures in Saskatoon, SK?

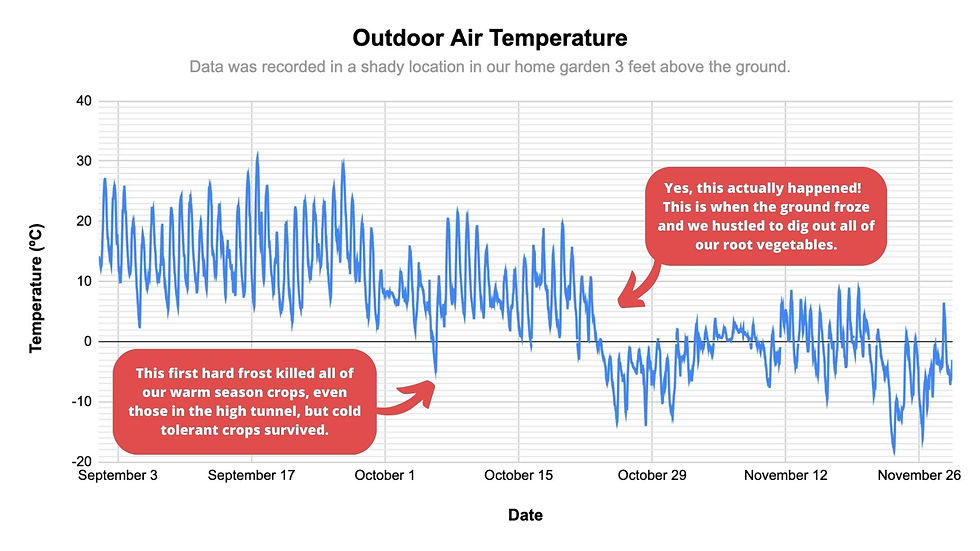

The temperature data from inside the tunnel wouldn't matter that much unless we could compare it to the outdoor temperature so let's start with that. The graph below gives you a look at our outdoor temperature from September 1st to November 29th this fall. Our first average frost is September 15th so you can see that we enjoyed a few extra weeks this year. However, that extra heat dissipated pretty quickly around the 22nd of October. When the daily highs stop rising above 0ºC, it doesn't take long until the soil is frozen, so we have to be quick about digging out our root crops when the time comes. Thankfully, we can usually see these extremely cold dips coming thanks to our local extended forecasts.

Now that we've set the stage with this first graph, let's have a closer look at a couple of dates to see how the low tunnel handled these dropping temperatures.

How well does a low tunnel protect our crops during a hard frost?

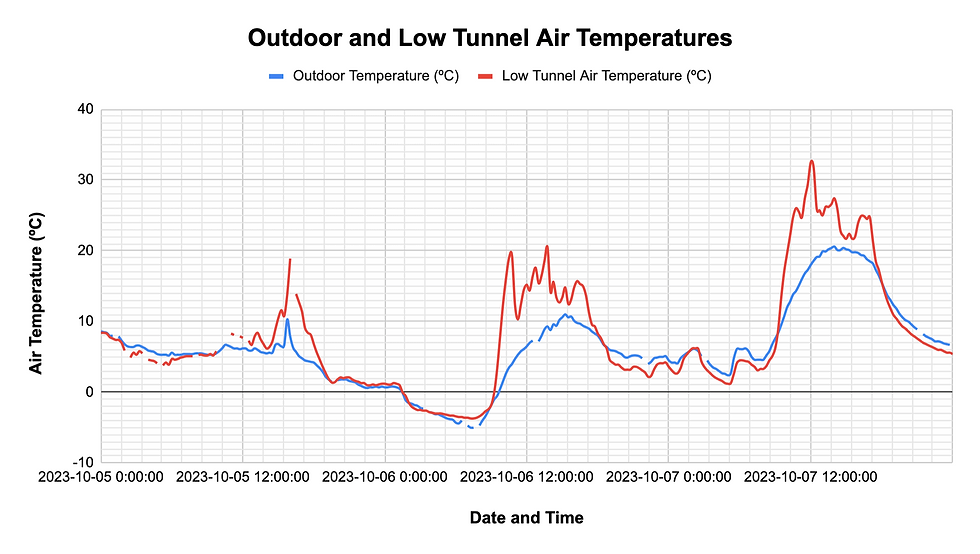

The first hard frost came on October 6th, and I was curious what happened under the low tunnel that night. This next graph tells the story. You can see the October 6th low right in the middle of the graph, and the low tunnel temperature is only 1.5 to 2ºC above the outdoor temperature.

While the data from that first night on October 6th was reasonable, there is something unexpected going on the next night when the low tunnel temperature is consistently lower than the outdoor temperature. How can this be? The ground should be warmer under the tunnel at this point and with a solid cover of poly over the hoops, it doesn't seem logical that the temperature could be lower under the tunnel than it is outside of the tunnel. First, I questioned the accuracy of my sensors, so I added a second sensor in each location, but they seemed to be reporting the same temperatures. Next, my mind wondered about possible humidity differences. You have probably had the experience of stepping out of a swimming pool or shower and suddenly feeling cold. That's because of the evaporative cooling effect caused by the moisture evaporating from your skin. Could there be a similar evaporative cooling effect happening under the tunnel somehow, especially if the night was fairly windy? Maybe? On both nights the low tunnel humidity was around 96% but the outdoor air humidity was 10% lower on the second night dropping from 72% on the first night to 62% on the second night. If there was also more air movement in the tunnel due to windier conditions on the second night, could that explain the colder air temperature under the tunnel. I don't know. There was also a difference in location. The outdoor air sensors were hanging in our backyard, and the low tunnel was set up in the boulevard which is more exposed to the wind. There are a few different factors here, and I don't have all of the answers at this point.

Can a low tunnel turn average November days into suitable growing days?

After looking at that first hard frost, we can see that a low tunnel of clear 6 mil plastic has pretty minimal protection against low temperatures. The real strength of plastic tunnels is in their ability to retain heat when the sun is shining. With this in mind, perhaps the best use for a low tunnel in fall is not to guard against all frosts, but rather to create a microclimate that could extend the growing conditions of our cold hardy greens, such as spinach and kale? These crops might still freeze regularly under the tunnel, but during the day, the temperatures could warm up substantially, allowing continued growth.

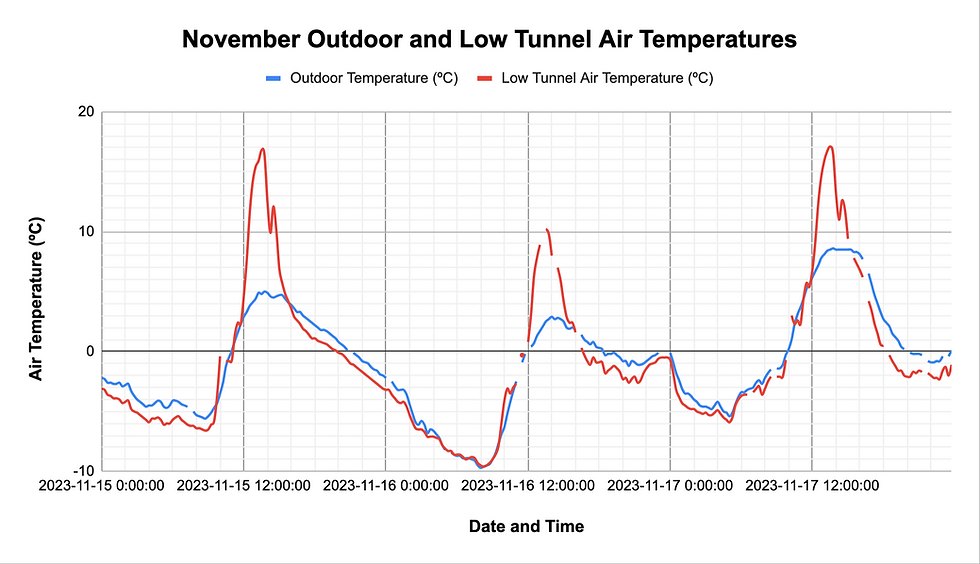

To answer this question, let's look at some data from a few typical days in November.

From this data, we can see some significant limitations of our November growing conditions. The tall red peaks show us that the tunnel still retains its ability to significantly increase the enclosed air temperature even when the sun is much lower in the sky. That's great, but the peaks are much more condensed than they were earlier in the season, and it's not that helpful to get a tunnel up to 15ºC if the temperature only stays in that range for 2 hours a day. We can also notice from this graph that the nighttime lows are considerably colder and the tunnel seems to be no help in defending our plants against these lows. In fact, we continue to see this surprising cooling effect of the tunnel, evident by the more rapid drop of the red lines each night. What is up with that? As usual, more knowledge leads to more questions.

Anyway, it's clear that our low tunnel can't magically turn a frigid November day into anything of value. Is it the tunnels fault? Partially. A layer of poly doesn't seem to have much insulating ability so the heat retention ability of a tunnel requires that the soil has some warmth left to dissipate into the air throughout the night. A huge contributing factor to the weakness of tunnels in the fall is the shortening of our days. Our summers are warm because of the increased intensity of the sunlight and the longer days. When we lose that heat energy and light in the fall there is not much left to work with, tunnel or no tunnel.

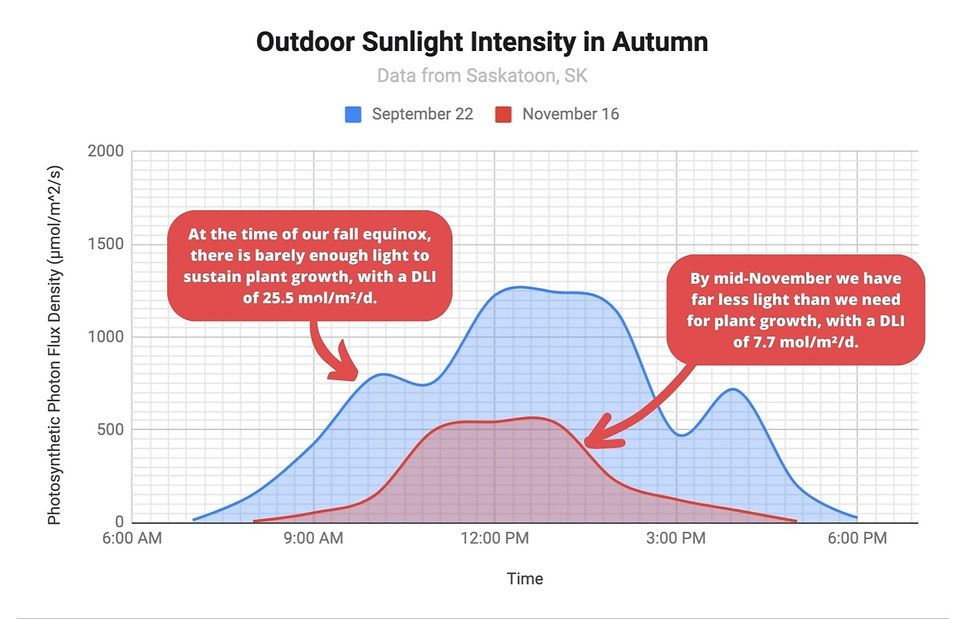

This limiting factor of light is a big deal in our northern climate, so I pulled out my light meter to take some readings and show you what we're working with here as our hours of daylight dwindle in fall. The curves you see in the graph below basically show you the total quantity of sunlight our garden receives in each square meter throughout one day. The way that this graph is drawn makes the data look like two piles, and you can literally think of it that way. Every rectangle underneath the blue and red lines represents a measured quantity of light that fell on our garden on those days. The piles start off pretty low early in the day when the sun is barely above the horizon and the piles grow considerably in the middle of the day when the intensity of sunlight is at its highest. If we count the total number of rectangles under each curve and do a little math, we can determine the total amount of light that fell on each square meter in our garden on one day. That information can tell us whether or not we are getting enough light to grow our vegetables.

You can see from the graph that the blue pile is much larger than the red pile. This is not because it was cloudy on one day and sunny on the other. Both days were pretty sunny aside from the two cloudy periods shown by dips in the blue curve. The main reason for the difference in the amount of light on these two days is just the changing angle of the sun and decreasing number of daylight hours we have as we get close to our winter solstice on December 21.

Now that we have data like this, we can answer the question of whether there would be enough light to sustain plant growth. According to research I have cited earlier in my post called "A Definitive Grow Light Study", the minimum amount of daily light needed to grow a shade tolerant crop like lettuce is 15 mol/m²/d while warm season crops like tomatoes, cucumbers, or peppers would require a total light quantity in the 20-30 mol/m²/d range. That total light quantity also needs to be received by the plant over a period of at least 10 hours, so even if our November light was more intense, the 7 hours of full sunlight wouldn't cut it.

Okay, so there's no hope of continuing vegetative growth late into fall for us even with a low tunnel, but perhaps the tunnels could still help us keep crops alive longer in a type of living refrigerator. To consider this possibility, let's look at how well the spinach and kale faired under the tunnel this fall.

These first two photos show the beds of spinach and kale on October 23rd. This is right before the big dip in temperature that you saw on the very first graph earlier. Spinach can survive some hard frosts but it can take some time to come back to life and the quality suffers so I did one large final harvest so we could enjoy this crop in its finest state.

These two hardy greens survived several frosts through late October, but by mid-November, they are starting to look a bit tired. The kale is not normally so droopy, although the leaves still had pretty decent stiffness and texture at this point, and the spinach hasn't grown much more since our full harvest on October 23. You can see some nice smaller leaves at the centre of the spinach plants but with such poor growing conditions there is very little increase in size.

And finally, just before writing this post, I snapped one final photo of the kale in its current state. It's now even more floppy than a couple of weeks ago, and the leaves are quite soft. However, they are still quite green. When this crop dies, the leaves brown completely. So I'd consider this still edible for many uses, just not the same quality that we're used to.

The best quality kale that we have right now is the large batch that we harvested over a month ago now on October 23. These kale leaves went straight into our walk-in cooler and have remained in pretty stellar condition. No, they aren't supported by their root systems anymore, but they also haven't had to endure many freeze and thaw cycles. As a result, their overall condition is superior to the kale leaves we still have in the field.

Summary

I realize the information in this post may have burst the season extension bubble for some of you. That's good though, because the alternative is that you spend a bunch of money and time working on season extension plans only to learn after the fact that you don't have enough sunlight and heat to keep anything alive. That said, many of you are in warmer climates and when your winters aren't as harsh as ours, a tunnel could be the difference needed to keep your crops alive and accessible for a couple of extra months or even right through the winter.

To wrap up this post, I'll end with the major takeaways I have gleaned from our low tunnel data and observations this fall.

Low tunnels are excellent for increasing the enclosed air temperature whenever sunlight is available. The best time for this is the early spring when the days are already long, or the early fall before the hours of daylight have shortened too much.

Low tunnels offer little frost protection and that degree of protection requires that the covered soil has been pre-warmed during the day.

Low tunnels are still valuable for enhancing growing conditions significantly before hard frosts are a threat.

Low tunnels are still valuable for keeping heavy snow off of useable crops late into fall.

Can low tunnels enable you to grow vegetables into winter? That will depend on your local climate. I can only sum up the value of low tunnels for us here in Saskatchewan, where we face quickly dropping temperatures and dramatically reduced light in fall. I hope this discussion has been helpful for you, but remember that your conditions will vary and it's only by practicing extending the season in your own garden, that you'll come to understand the true value of low tunnels in your context.

.png)

.png)